Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 53, No 4 - Winter 2007

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 53, No 4 - Winter 2007 Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas |

| Whitehorn’s

Windmill (An Excerpt) Kazys Boruta Translated from Baltaragio malūnas, ar kas dėjosi anuo metu Paudruvės krašte. Vilnius: Vaga, 1996. Translated by E. Novickas |

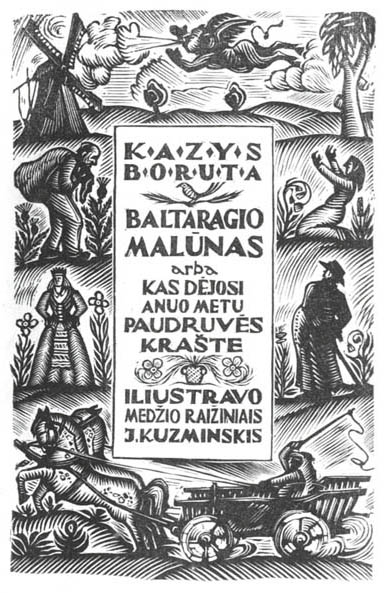

Title page from Boruta’s 1945 edition of Baltaragio malūnas, published in Kaunas, Lithuania. |

[See also "Translator's Reflections ..."]

That sanctimonious old biddy Uršulė – that gnarled and sour little woman, eternally dissatisfied and as mean as a hornet, returned to the mill one morning at dawn covered with muck from Paudruvė’s bogs and then, scolding all the while, fled Whitehorn’s house, where she’d been housekeeper since time immemorial, and moved into Svendubrė’s Sanctuary for Pious Ladies, so that such dreadful things wouldn’t happen any more.

She held Whitehorn responsible, claiming that he, the old sorcerer, wanted her, a maid sworn to chastity, to make a match with none other than the devil himself, who had long since lived in Paudruvė’s bogs and went by the name of Pinčukas.

What really happened – no one could say, and Uršulė herself wasn’t telling the whole truth, since in fact she didn’t understand it all herself, or if she did, then her old maid’s modesty wouldn’t let her say. It was just that one day, when her patience with knocking about the old miller’s house had run out (in fact she’d lost her last hope of marrying Whitehorn and becoming the miller’s wife, something she had been dreaming about in vain for a long time), a sin occurred – quite unintentionally, the terrible words had sprung from her lips, that she would take the devil himself, if only she wouldn’t have to waste any more time at Whitehorn’s house, where her youth had withered in vain.

Upon hearing these words spoken in frustration, Whitehorn was, for some odd reason, pleased, and even cheery, which was a rare thing with him.

“Very well,” he said, “I can arrange it. Our neighbor Pinčukas is rotting away in the bogs without a wife.”

Shocked, Uršulė crossed herself and then made the sign of the cross over Whitehorn.

“Begone!” she said. “Don’t you know I’ve made a vow to live in chastity?”

Then Whitehorn laughed and merrily declared:

“That’s nothing,” he said. “Vows are vows, but when you lay your eyes on a suitor with a matchmaker, you’ll forget all about them.”

Uršulė was put out and stopped talking to Whitehorn, but then again, Whitehorn didn’t miss her chatter; he merely went on about his business. He went about mysteriously, with a cunning smile, as though he was getting ready to deceive someone and the very thought cheered him.

The treachery wasn’t long in coming. The next Saturday evening, at sunset, matchmaker’s bells began ringing. Those bells always went straight to Uršulė’s heart, and now she stopped in the middle of the yard, waiting to see which farmstead the matchmaker would pull into. It never even occurred to her to think of herself; instead she thought of all the richest and prettiest brides in Paudruvė, but behold – the matchmaker went by the mill and turned in just exactly there.

“Are they lost?” This thought cheered Uršulė because she was eternally furious with the matchmakers, since they had never once arrived with a suitor for her.

At that very moment, while Uršulė stood gaping in surprise but rejoicing that the matchmakers had lost their way, the bay steeds flew into the yard and a gilded carriage stopped by the little rue garden.

“What’s this now?” Uršulė even felt faint.

Out of the carriage stepped one serious gentleman with a gray beard and a young gentleman with a smart little hat. Both of them bowed to Uršulė, and the older one asked:

“Is this, by any chance, Squire Whitehorn’s renowned estate?”

“Oh no, sir” said Uršulė, more dead than alive, “It’s just plain Whitehorn, and it’s not an estate, it’s a mill.”

“Just what we need,” said the graybeard, and bowed even lower. “Will you take in some travel-weary visitors?”

“You’re very welcome,” answered Whitehorn, who appeared from the mill, “We’ve been waiting for our honored guests for quite some time.”

Whitehorn led these unusual visitors to the parlor, while Uršulė hid herself in the pantry, terribly ill at ease. Could her long-awaited prince have arrived at last?

In the meantime, the gray-bearded matchmaker, barely setting foot into the parlor, without even taking a seat, still standing by the door, started in on his speech:

“I’ve driven by the lakes, past the bogs, and I found a little rooster,” he said. “The little rooster crows and fusses, he’s looking for a speckled hen... perhaps we will find her here?”

“Exactly so,” answered Whitehorn, and he led Uršulė out of the pantry. “Isn’t this the one you’re looking for?”

“The very one,” answered the pleased matchmaker, while the suitor crowed with joy like a rooster and spun around in a circle.

Uršulė blushed then, as red as a poppy, and couldn’t utter a word. She glanced out of the corner of her eye – the suitor was unspeakably handsome. Her heart throbbed; she couldn’t hardly keep her feet, her eyes were somehow dazzled.

The couple was seated at the table, upon which immediately appeared the appropriate bottle decorated with a green sprig of rue. What happened after that in the parlor Uršulė herself would never quite remember, as if some madness had come over her, or she had completely lost her head. Later she understood that it was all a plot by that old sorcerer Whitehorn and his friend, Pinčukas of Paudruvė’s bogs, to ruin her chastity.

But at the time Uršulė, as if in a stupor, didn’t understand a thing, and she only recalled that she drank sweet mead (just where had that come from?) with the long-bearded matchmaker and her heart swooned from the suitor’s loving words. She was so happy, more so than she had ever been in her life (truly she had been bewitched!), so that she didn’t have the slightest idea of how long it all took. Only later did she remember, as if in a dream, how she had left the parlor swooning with happiness, the gray-bearded matchmaker leading her by one arm, the suitor by the other, and he so handsome, so loving, you couldn’t have imagined it even in your dreams. Behind them followed that shameless Whitehorn – a distant relative, but worse than an enemy! – smiling treacherously and looking pleased about something, but to Uršulė he might as well not even have been there. It was just that while she was leaving, she noticed the suitor gave him some sort of paper, which he cheerfully tucked into his jacket. Probably it was then that he had sold her chastity, while she, poor thing, didn’t understand a thing.

Stunned in this way, Uršulė was planted in the gilded carriage; next to her on the right sat the graybeard, and on the left – the gallant suitor. The bay steeds hardly stood still by the porch, their ears twitched and their eyes flashed lightning. The matchmaker said:

“We’re off for the banns!”

“Best of luck!” Whitehorn wished them.

The bay steeds leapt from the spot like dragons, the ground thundered, and the carriage flew off as if caught up in a whirlwind. Startled and frightened, Uršulė didn’t even have time to shed a tear for her maidenhood. Everything happened so quickly.

It was merely Uršulė’s good fortune that she managed to cross herself in her fright. Then lightning flashed across the heavens, and suddenly everything vanished. Neither the carriage nor the matchmaker with the suitor remained – it was as if they had never been, and the startled Uršulė found herself in the middle of Pinčukas’ swamp, having fallen out of a feedingtrough and sunk up to her armpits in duckweed. Not only that, but something was janking at her terribly by the legs, intending to submerge her entirely.

It was then that Uršulė understood to whom Whitehorn had wanted to betroth her, and she began shouting for the intercession of all the saints, and particularly the Virgin Maiden of Svendubrė, to whom she had made her vows and who sheltered innocent maidens and guarded their chastity. But perhaps because Svendubrė was too far away, or because it was a dark, stormy night, Uršulė’s cry was answered only by a hellish cackling, and with her very own eyes she saw the devil of Paudruvė’s quagmire, Pinčukas.

“Scream, or don’t scream,” he said, rising up as suddenly as an apparition, “It won’t make any difference. You were promised to me a long time ago and you’re going to be mine.”

Pinčukas made a move to lovingly hug his betrothed and kiss her, but Uršulė angrily shoved him away.

“What do you mean, I’m yours?” she said, absolutely incensed. “Who could have promised me to you?”

“Whoever promised kept his word, and you stop shoving!” answered Pinčukas, who, as if pretending to be bullying or teasing, impudently tugged at Uršulė’s full, pleated skirt.

This was an inexcusable impudence on Pinčukas’ part, for which he was justifiably punished. The indignant Uršulė suddenly turned around and gave him such a smack on the cheek that Pinčukas fell to his knees, hooked his horns on her skirt, and pulled it over his head. The frightened Pinčukas wanted to get out from beneath that pleated skirt as fast as possible, but in his haste, as could be expected, he managed to entangle himself even further in the pleats, and tumbled down at Uršulė’s feet.

So Uršulė, without pausing for a moment even though she was left without her outermost pleated skirt (fortunately, she was wearing nine of them), just dreadfully infuriated, lit such a fire under Pinčukas, that he whined and whimpered but he couldn’t escape from under that skirt. Perhaps Uršulė would have completely trampled Pinčukas, except that he, having no other choice, tore through the pleats of the skirt and dived for the bottom of the quagmire, pulling Uršulė down after him.

At last, wallowing in the swamp, Uršulė seized a juniper bush with her left hand and with her right hauled the muddy Pinčukas out of the duckweed. She wanted to get her hands on him again, but he broke free and started tearing about, squealing and whining but still not backing off. Then Uršulė, gathering her last strength, crawled out of the swamp, took the rosary with scapulars off her neck and started to scrub Pinčukas with them, letting the blows fall where they might – on his eyes, on his horns, on his flanks, on the backs of his knees. He was writhing as if on hot coals, running about through the swamp as if his pants were on fire, but the raging Uršulė wasn’t more than a step behind. She went stumbling behind him through the bogs, blessing him with her rosary and doing the honors by every means possible, so that at last the poor little devil couldn’t take it any more, swore and said:

“Nine poxes on you, you witch! I don’t want you anymore. Begone from my sight!”

“I’ll begone you!” growled Uršulė and grabbed Pinčukas by the horns.

Uršulė wanted to throw the torn pleated skirt over his head again, wind her rosary around his neck and drag him back to Whitehorn, so that he could see, shameless creature that he was, what sort of a suitor he had wanted to fix her up with. But then the roosters in the village began to crow. Pinčukas shook himself and disappeared as if he had never been. Uršulė was left with a piece of bark in her hand, perhaps from a juniper root, and her torn skirt remained snagged on a bush. What could you do with it, defiled and shredded as it was by a devil? Uršulė, spitting, slung the piece of bark away, too.

Then Uršulė floundered through Paudruvė’s bogs until dawn, terribly vexed and unable to extricate herself. It was only at daybreak, as furious as a witch and completely muddy, her remaining skirts pulled up to her knees, that she returned to Whitehorn’s mill.

It was Whitehorn’s good fortune that he heard the sanctimonious old biddy coming home fuming from the bog (perhaps he wouldn’t have, if not for Pinčukas running back earlier in fright), and managed to hide himself in time in the mill with the door bolted shut from inside. He would have gotten the heat, too, no less than Pinčukas, or perhaps even more so – for her wilted youth and the revolting mockery.

Unable to barge into the mill and vent her frustration on that malicious creature’s head, Uršulė just stormed through the yard cursing with all her might, and then, as if coming to her senses, she ran into the cottage, wrapped up her clothes into a bundle, and tore off at a run down the slope towards Svendubrė. As she ran, she kept turning back to shake her clenched left fist threateningly in the direction of the mill, while with the similarly clenched right one she crossed herself, and all the while a stream of maledictions flowed.

“The old biddy’s gone completely off her rocker,” thought Whitehorn, watching the receding Uršulė from the little window at the top of the mill. “It seems even the devil couldn’t manage to keep hold of her.”